Why Liquefied Natural Gas?

How did Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) come to be seen as viable fuel source for ships? Why is a refinery and storage tank being built in the Port of Tacoma? To answer this, let’s first go back a few steps and look at how various fuels are made from crude oil.

Origins of Fuels

Crude oil, or petroleum, is what Exxon, Chevron, BP, and other oil companies around the world are busy digging, pumping and drilling out of the earth. In this raw form, however, it’s not very useful as it’s a messy mixture of different hydrocarbons, which are simply chemicals made of hydrogen and carbon atoms. Most of these burn really well and that is why they now power most of the world. The simplest of these is methane (CH4), the primary component in so-called “natural” gas, but science says they can form “seemingly endless” chains of carbon and hydrogen. Some of the more simple ones, containing up to 10 carbon atoms, make up the more important fuels like the gas for our cars and the jet fuel in our planes.

But how do they sort them all out? Turns out that all these chemicals have different boiling points and can be separated by distillation. Basically they get the crude oil really hot in a tall container and all those hydrocarbons obediently organize themselves. Light ones, like propane and butane (C3H8 and C4H10) bubble up to the top while other ones found in diesel stay closer to the bottom. All of these are called distillate fuels. Generally the higher in the tower the higher the market price.

Some of the long hydrocarbons don’t boil at all and stay at the bottom of the tower. These are called residuals. They burn dirty and are inexpensive. Sometimes refineries will use a process called cracking to break these up into more valuable distillate fuels, but residuals can be used for tar, asphalt, paraffin wax and, you guessed it, ship fuel.

Types of Ship Fuels

Ship fuels come in different qualities, from Marine Gas Oil (MGO) which is a pure distillate fuel (relatively clean) to Heavy Fuel Oil (HFO) which is all, or nearly all, residual fuel (very dirty). The grades in between simply differ in the ratio of these two. While all ships “bunker” their fuel (the name of storage tanks on ships), “bunker fuel” usually refers to Heavy Fuel Oil as it is the most common type.

Unfortunately for the environment and for human health, HFO burns very dirty and spews out tons of toxins, among which sulphur oxide receives particular attention. And big ships use a lot of HFO – one of the largest container ships in existence, the Emma Maersk burns up to 380 tons per day.

Back around 1950, the United Nations wanted to better regulate the shipping industry and formed the International Maritime Organization. By 1973, the IMO started addressing the pollution issue and created the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, commonly called MARPOL. Ever since then environmental regulations have been growing steadily more protective.

In 2005, the MARPOL regulations on air pollution entered into force and began limiting sulphur oxide, nitrogen oxide and and particulate matter from ships. Globally speaking, ships must burn fuels with no more than 0.5% sulphur content by 2020 (actually pending a feasibility study in 2018, which could knock compliance date out to 2025). Some regions, called Emission Control Areas (ECAs), are even more strict and currently allow sulphur contents of just 0.1%. The waters around the continental US and much of Canada are one such region.

This essentially means that ships can no longer burn heavy bunker fuel near the U.S. right now and, soon, across the entire globe. It turns out it’s difficult to make low sulfur HFO because it’s largely dependent on from where the crude oil originated.

To put ship pollution in perspective, it has been calculated that one large ship burning HFO can pump out as much sulphur in a year as 50,000,000 cars. The IMO says these new regulations “should have major health and environmental benefits for the world, particularly for populations living close to ports and coasts.” One study says that were sulphur not restricted, “air pollution from ships would contribute to more than 570,000 additional premature deaths worldwide between 2020-2025.”

Shipping companies want to continue burning HFO because it is inexpensive and MGO is not, in comparison. Thus, they are eager to secure a less expensive fuel source that still meets the emission regulations defined by MARPOL.

Enter so-called natural gas. Thanks to increased production from fracking, there is a large supply of the stuff on the market (it is often cited as the primary contributor to the downfall of the coal industry) . Composed primarily of methane, this fuel does not produce as many emissions as diesel, let alone HFO, when burned. More importantly, it meets the sulphur oxide, nitrogen oxide and particulate matter regulations.

As a gas, methane wouldn’t store very well on power-hungry ships – it doesn’t have good energy density. Cool it down to -260 F, though, and it condenses into a liquid and occupies 1/600th the original volume. It’s now LNG, or Liquefied Natural Gas. Even then it’s still not as energy dense as diesel and thus limits the sailing range of ships. But it’s still cheaper than MGO.

Origins of Tacoma LNG

For some shipping companies, LNG looks like a great solution. Totem Ocean Trailer Express, or simply TOTE, is a company that has short, regular shipping routes that are primarily in US waters and thus in the strict ECA. One route goes between Jacksonville, Florida and San Juan, Puerto Rico, the other between Tacoma, Washington and Anchorage, Alaska.

Years ago TOTE realized complying with the incoming ECA standards would be expensive. Once they hit upon LNG they asked the EPA if they could be exempted from these standards while they transitioned. The EPA granted them an exemption from August 2012 to September 2016, (meaning they willingly burned dirtier fuel throughout those four years). Since the end of that exemption they would have started using MGO and are simply charging their customers an additional fuel fee.

In 2015, TOTE received delivery of a custom ship, the world’s first LNG powered container ship. Both ships on the Puerto Rico route now use LNG and they found a supplier in Florida by the name of Pivotal LNG.

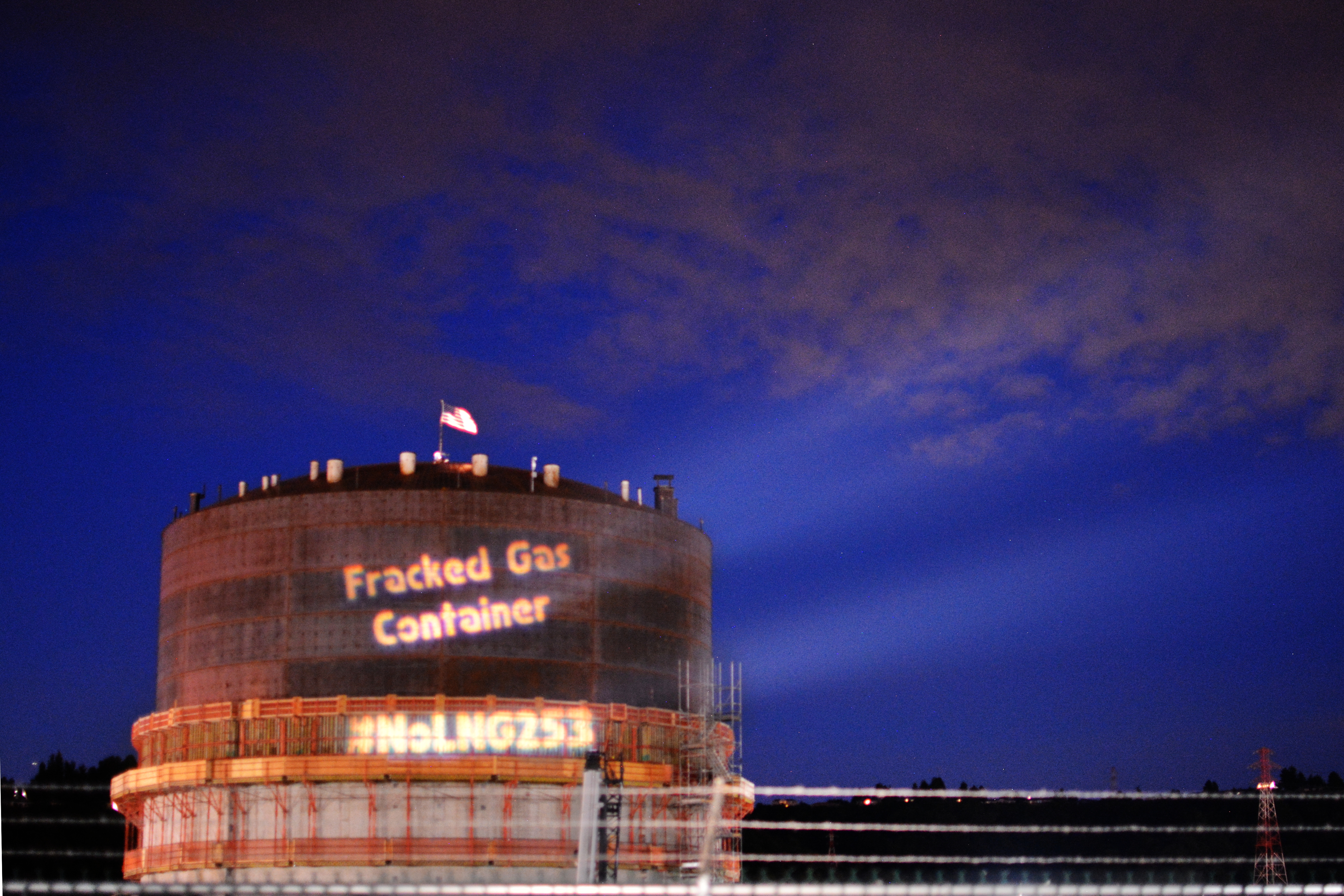

Wanting a similar supply in Tacoma, TOTE put out a Request For Proposals (RFP) and accepted Puget Sound Energy’s bid in 2013. That facility, as of February 2018, is currently under construction in the Port of Tacoma. The two ships on the Tacoma-Anchorage route have yet to be converted to use LNG, and that conversion has now been pushed back beyond 2021 because of delays in the Puget Sound Energy (PSE) LNG permitting process.

Puget Sound Energy, an Australian-owned, for-profit business but also a state-backed monopoly supplier of natural gas in western Washington, is only too happy to find more customers for their gas (they buy on the open market), some 50% of which could come from fracking. They also cleverly pitched the facility as a peak-shaver, meaning it could be used to provide heating gas to homes in Tacoma on the coldest days of winter, thus justifying charging their ratepayers for a portion of the facility. The numbers don’t compare though – ratepayers may only see 7% of the use of the facility, yet are being saddled with 43% of the construction costs. This doesn’t even consider the numerous corporate welfare tax breaks.

LNG as a maritime fuel isn’t widely available – there are only a handful of locations in North America (if you include Tacoma) to fuel up and only around 120 of the world’s 100,000 ships consume it. TOTE, for some reason, doesn’t want to stop there, however. It is part of an international movement to have LNG become the next major maritime fuel and, in their own words “help lead to the proliferation of natural gas as a transportation fuel.” Their president, Peter Keller, is the Chairman of the Board of SEA/LNG, an advocacy group, which aims to “accelerate the widespread adoption of liquefied natural gas (LNG) as a marine fuel.”

The push for maritime LNG is linked tightly to the PNW. Not only does TOTE run two of its ships from Tacoma, but is itself a subsidiary of Saltchuk Industries, a Seattle-based family-owned company with $2.75 billion in annual revenue. It owns many businesses, including Foss that operates tugs here in Tacoma, Northern Aviation Services, Tropical Shipping and North Star Petroleum. Fred Goldberg, who helped found Saltchuk, is the Vice Chair of the Board of Trustees of Evergreen State College.

PSE’s CEO, Kimberly Harris, lives in Bellevue and is Chairperson of the Board of Directors for the American Gas Association (AGA), which represents distributors of 95% of the “natural” gas sold in the U.S., homes and industry included. The AGA claims the gas they sell represents one-quarter of energy consumed in the U.S., and surely they would love to increase that share by fueling ships as well.

Is LNG a cleaner fuel or not?

If you measure for pollution coming from the exhaust of a ship’s engine, then LNG is a cleaner fuel than Heavy Fuel Oil and even Marine Gas Oil – it has less sulphur oxide, nitrogen oxides, particulate matter and even CO2. Many in industry like to claim that it’s a “bridge” fuel until we find a viable renewable source. Unfortunately that’s where the good news ends.

Again, LNG is composed chiefly of methane, which is itself a nasty greenhouse gas – 86 times worse than CO2 over a 20 year span, and 36 times worse over a 100 year span. New research actually suggests that those numbers may be underestimated by as much as 14%. This means that we don’t want to be adding any more methane to the atmosphere and, in fact, scientists point out that we can have more immediate impacts on lessening climate change by reducing methane since it doesn’t last as long in the atmosphere as CO2. Alarmingly, US methane emissions have risen 30% in the past decade thanks mostly to the central US, a hotbed of fracking.

The entire life cycle of LNG needs to be taken into account to determine if it is better than even MGO. Because methane is so potent a greenhouse gas, it doesn’t take much to leak out in the drilling and fracking process, the distribution network, the storage tank, or the ship to make it worse for the climate. Some scientists estimate that it would only take 3% of fracked methane to leak to make its overall effects worse than coal. Does that much leak? Unfortunately they estimate between 3.6-7.9% leaks into the atmosphere during shale drilling operations alone. The International Coalition for Clean Transportation estimates 2.2-4.6% of methane on ships escapes into the atmosphere after passing through the engine without combusting. This is known as methane slip and its rate depends on the type of engine.

Natural gas leaks can be just as catastrophic for the environment as oil spills. Remember the leak in Aliso Canyon, California? Natural gas stored underground in a depleted aquifer gushed out into the atmosphere for 118 days straight before being stopped. Around 5.2 billion cubic feet of methane was released into the atmosphere (or about the same amount of fracked gas stored, in liquid form, in the PSE LNG facility). It’s overall effect on the environment is rated as worse than the BP horizon disaster in the Gulf of Mexico. PSE operates a similar facility, called Jackson Prairie, about 70 miles south of Tacoma.

MARPOL is working on GHG measures for ships but this is a work in progress. In April of 2018, they adopted a “vision” to reduce GHG emissions from shipping by 50% by 2050, while “pursuing efforts” to phase them out completely.

What is the future of maritime shipping?

While the answer to this question is not yet clear, what is certain is that we can’t continue with business as usual, nor can we waste anymore time on “bridge” fuels like LNG. There are some exciting possibilities on the horizon and government and industry should be pouring their resources into developing those, rather than propping up the fossil fuel industry.

Great strides have been made in battery technology in recent decades and a new breed of ships is already taking advantage. Even here in the Puget Sound, our ferry fleet seems poised to take the leap to renewables, with a test on a car ferry from Anacortes perhaps leading the way for the fleet. For this application, with short distances, dedicated home ports, and an abundant supply of hydro power, batteries seem perfect.

Further afield, China launched the first battery powered cargo ship in November 2017, and the Netherlands is developing an inland battery powered barge.

Hydrogen fuel cells present another option for ship power, assuming the hydrogen itself is produced using renewable energy (currently only 4% is, with 50% coming from, unbelievably, “natural” gas). Since 2009, Germany has been running a 100 passenger hydrogen ferry called the FCS Alsterwasser. Representing a huge leap in scale, Viking Cruises announced in December 2017 plans for a hydrogen powered, 900-passenger cruise ship.

There are also companies like Bound4Blue who produce modern-day sails for cargo ships and tankers that aim to achieve 30% savings in fuel use. To create hydrogen, they propose a fuel-generating ship pushed by sails, and the movement of the ship would drive underwater turbines. Those turbines would in turn produce electricity to create hydrogen from seawater by electrolysis, which is simply using electricity to separate the hydrogen and oxygen atoms in molecules of water.

Even Wallenius, which ships rolling equipment like automobiles, has found that LNG is not the right solution. On their roadmap to a zero emission future, they are incorporating sails like those made by Bound4Blue.

Conclusion

LNG appears to only have emissions advantages over “traditional” maritime fuels when examined at the point of combustion. Once the entire life cycle of LNG – from extraction through distribution to final usage – is taken into account, it is clear that LNG is even worse for the climate than coal.

Given the increasingly strict point-source emissions standards for ships and the recent surge in natural gas extraction, it is understandable how LNG came to be seen and marketed as a so-called “bridge” fuel by those wishing to turn a profit off their existing infrastructure.

However, we can’t afford to continue using the “traditional” fuels indefinitely if we wish to maintain a stable climate and avoid untold human and animal suffering. That is why it is more important than ever to invest in emerging carbon-free shipping alternatives that utilize batteries, hydrogen and rigid sail systems. At this point in history, investing in new fossil fuel infrastructure like LNG for shipping is not a bridge to a carbon-free future, it is a prison locking us into years of continued usage.

A great way for Tacoma to reduce GHG emissions in the port quickly would be to provide and mandate shore power connections for all visiting ships. Right now, ironically enough, only the two TOTE ships plug into electricity while in port – the rest continue burning fuel for their generators while alongside. The port could also electrify its truck and container moving vehicles as ports in California are doing.

There is discussion in the financial sector now about fossil fuel infrastructure becoming “stranded assets” – infrastructure that could lose money for investors or companies due to increasing regulation and concern over climate change. The PSE LNG facility in Tacoma carries a risk of being one such stranded asset.

Investing in fossil fuels in 2018 is like betting on candles at the dawn of light bulbs, horses in the early days of the automobile, or pagers during the emergence of smartphones.

We don’t want Tacoma stuck in the dark ages of fossil fuels.