By Kiernyn

On the evening of Feb. 24th, 2020, the headquarters of 350 Tacoma played host to a valuable and intersectional reading. The eight presenters came from a variety of backgrounds, spanning gender, race, income, geography, and ability. But two things united them – they had experienced hate at some point in their lives, and they were committed to addressing these moments through the written word.

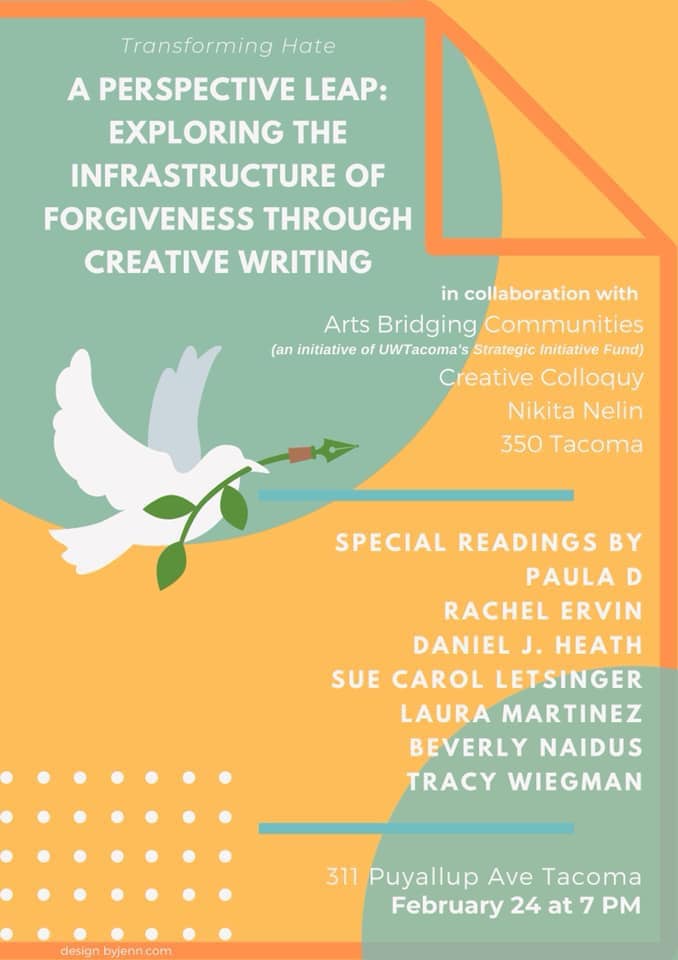

Several weeks previously, the readers had participated in a workshop titled “Transforming Hate – a Perspective Leap: Exploring the Infrastructure of Forgiveness through Creative Writing” taught by Nikita Nelin. This series, open to the public, was a collaboration between local literary group Creative Colloquy, 350 Tacoma, and Arts Bridging Communities, a group affiliated with the UW Tacoma that seeks to increase public connection to the arts via workshops, performances, and community events. The reading offered a valuable chance for the workshop participants to present and discuss their work with a larger audience, and for the audience to engage with the ideas covered in the workshop.

The event began with an introduction by Jackie Casella, the founder of Creative Colloquy. “The theme this evening really drives home how cathartic and constructive writing can be,” she explained. Next was a brief speech by Nelin, detailing the origins of the workshop and its aim of fostering forgiveness and healing. He emphasized that the endeavor “[I]s foremost a living project.” The idea was sparked in a previous workshop, when some participants asked him a simple but confounding question: “How do we forgive?” Unable to formulate an answer, he decided to explore the idea further. The resulting workshop was a deeply personal project, one that explored trauma and confronting it through the lens of personal writing. While the process involves a great deal of introspection, Nelin highlighted the tremendous levels of courage and vulnerability involved, as participants shared their deepest pain with one another. It was something, he emphasized, that seems critical to social justice. “It seems to me that whatever comes next – if there is a next – must be some form of reconciliation,” he said. “I cannot name the shadow. I must ask it to name itself.”

Nelin ended his speech with memories of his youth in the Soviet Union, when intense public censorship led to crucial conversations being held in intimate, domestic spaces. “This workshop […] is the descendant of those kitchen revolutions,” he explained.

Next up were the readers, each offering their own unique take on the prompt. Beverly Naidus, an artist-activist and professor at UW Tacoma, chronicled her childhood encounters with anti-Semitism and her ever-evolving, often challenging relationship to her Jewish identity.

Laura, a nurse, recalled her culture shock going to school in the Midwest after growing up in East L.A., as well as the continual racism and classism directed at her by classmates and administration alike. As she put it, “My success was my revenge.”

Tracy, a long time dockworker, discussed her history of abusive partners and her work, via therapy, to understand the patterns both as part of a story stretching back to her childhood and as something connected to a greater grief over the ecological and cultural destruction wreaked by the border wall. Yet there was also optimism, expressed in both her environmental activism and her bond with her children. “In everything we do,” she advocated, “include love.”

Paula, a massage therapist and founder of TrashTalkTacoma, read a poem about coping with assault and the powerful, necessary decision to reclaim some control by speaking out. Although all of the lines were brutally honest and beautifully compelling, two in particular stood out: “I hate the secrets that hold us down as less than them,” and “Who am I to spend my time unseen?”

Roberto, a self-described “second-generation immigrant and occasional writer,” took the audience on a journey through time past the ghostly imprints of racist figures from his past, analyzing the moments when they forewent compassion side by side with their more human aspects. Some, such as school officials, were able to be forgiven, while others, such as ICE agents, were not, as they are mechanisms of a broader systemic harm. Roberto ended his piece by stating that “Hate is a memory older than myself,” and reinforcing that it is our responsibility to face it.

Daniel, a professor at Pacific Lutheran University, presented a reverse-chronological list of incidents in which the Pentecostal religion that was meant to save him became, instead, a bastion of intolerance, propagating bigoted views and punishing his innate scientific curiosity (itself an offshoot of his Aspergers, another aspect of identity which he grappled with in the piece).

Rachel, whose biography stated that she dreams of the extinction of billionaires and the health insurance system, vividly depicted the troubled socioeconomic status of the Central Valley of California, where she spent her adolescence. She closed the piece with a powerfully visceral passage from the point of view of the land itself, brutalized and over-farmed for centuries. “I used to be desert before all this green,” she lamented in its voice, before uttering the powerful closing line: “Let me keep those that leave me be.”

The final reader, soil ambassador and ecological activist Sue, presented a short but powerful piece on the ongoing consequences of wars – both military and environmental.

The evening ended with a panel discussion hosted by Dr. Sarah A. Chavez, a writer and faculty member at UW. The panel offered a wonderful chance for the audience to engage with the writers on individual aspects of their pieces, as well as broader inquiries into the impact of the workshop. There was a great focus on forgiveness and on the healing, bold, painful process of understanding others as we grapple with the damage they’ve inflicted. It faces marginalization and oppression with some of its most primal and emotional aspects.

And the work done looking outward had inward effects as well; Naidus said that “I developed compassion for my own wound… my scars became jewels.” The healing effects of engaging with a diverse audience were addressed as well; and indeed, in this author’s opinion, there was something particularly inspiring about the sheer multiplicity of organizations, ideas, and backgrounds that were represented at the gathering, all invested in the process of combating hatred in all its complex forms.

Towards the end, Nelin discussed the idea of continuing the workshops on a semi-regular, open-door basis, in order to continue the work that was done there. Ideally, they see it as a way to contribute to the same sort of positive progress that 350 has tried to frame in its own artful activism. As Naidus said, “We need to be able to use our writing and our image-making to reimagine the future.”